Nasa 4 umetnika

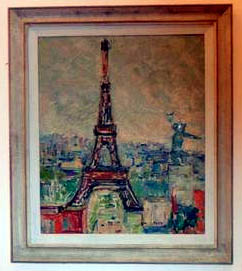

Mosa Pijade (Beograd 1890 - Pariz 1957)

U zatvoru proveo 14 godina, slikao uglavnom autoportrete, portrete drugova sa

robije i mrtvu prirodu.

![]()

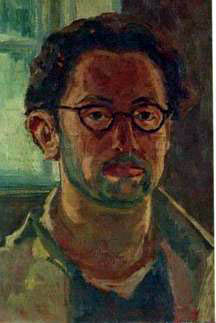

Leon Koen (Beograd 1859 - Vrsac 1934)

Najznacajniji predstavnik simbolizma u Srbiji. Zbog bolesti prestao da slika

rano, a na nesrecu skoro ceo opus nestao u ratu dok se najznacajnija dela cuvaju

u Narodnom muzeju (NMB).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Veciti Juda JIM | Autoportret NMB | Prolece JIM | Prolece NMB | Haron NMB | Jesen NMB | Pogrom JIM | Josifov san JIM |

Leon Koen je bio jedini izvorni slikar Simbolizma, rodjen (c. 1859) u

Beogradu, prestonici Knezеvine Srbije.

Odrastao je u jevrejskoj četvrti Jalija kraj

Dunava. Potekavši iz siromašne

mnogočlane porodice, u mladosti se izdvojio uočljivo strastvenim

doživljajem vidjenog. Poriv ga je preusmerio od krojačkog

zanata ka učenju crtanja u Beogradu. Usledile su i studije u inostranstvu,

po prijemu na Akademiju umetnosti u Minhenu u Bavarskoj posle 1882. Koenova

učenja u klasama Akademije sustigla je njegova krajnja posvećenost

istorijskim i verskim temama. Nagradjen je Srebrnom medaljom Akademije 1896, za

veliko platno ’Josifov san’ nadahnuto Starim zavetom. Sliku je potom

izložio na prvoj samostalnoj izložbi u Beogradu, a sa svojim delima je

ucestvovao i na prvom Bijenalu u Veneciji 1899, kao i u postavci srpskog

paviljona na Svetskoj izložbi u Parizu 1900. Koenovo poneseno

stapanje srpskih i jevrejskih predanja, grčkih mitova i šekspirovske drame

proisteklo je u evokativne teme kakav je ’Večiti Juda’ koju je naslikao

u vise varijanti. Živeo je povremeno u Beogradu, ali zbog studija pretežno u

Minhenu, boreći se sa oskudicom u

predanoj umetničkoj karijeri i prijateljstvima sa studentima i umetnicima

iz domovine, kao i sa Fon Štukom ili sa Kandinskim, s kim je izlagao na

izložbi grupe ’Phalanx’ 1903. Mnogi podaci o Koenu su nestali, izuzev

izveštaja Ministarstvu Prosvete Kraljevine

Srbije oko nedovoljnih stipendija. Nevolje su se pojačale mentalnom

bolešću posle 1905. Njegova supruga Jozefina Šimon prodala je ili

založila najveci broj slika, u vreme kada je Koen izgubio moć prisebnosti.

Posle Prvog svetskog rata, prijatelji oko

Jevrejske opštine vratili su ga iz Minhena u Beograd. Koen je ostao

bespomoćan do smrti 1934. Fascinacija ljudskim sudarom sa svevišnjim

silama može se razmotriti i skorijim otkrićem: bio je prvi prevodilac na

srpski uvodnog dela Ničeovog spisa ’Tako je

govorio Zaratustra’. Više od stotinu Koenovih likovnih radova nestalo je, nabrajaju

se razlozi: pustošenje Sinagoge Bet Jisrael i opštine 1941. kao i

nacistička okupacija Beograda. Na sve se, što je zanemareno, nadovezuju i

nejasne okolnosti za njihov nestanak posle

komunistickog prevrata. Zvanično, danas se svega 15 Koenovih radova nalazi

u muzejima u Srbiji.

![]()

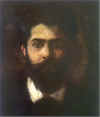

Daniel Ozmo (Olovo 1912 - Jasenovac 1942)

Jedan od osnivaca slikarske grupe Mladost, uljem i akvarelom slikao u duhu

poetskog realizma, napravio mapu linoreza iz bosanskih suma, crtao logorase u

Jasenovcu. Diplomirao je 1934. na Umetnickoj skoli u Beogradu u klasi profesora

Ljube Ivanovica. U Sarajevu je kratko radio kao profesor u Prvoj gimnaziji.

Streljan 5. septembra 1942 u Jasenovcu pod izgovorom da je "sirio uznemiravajuce

vesti".

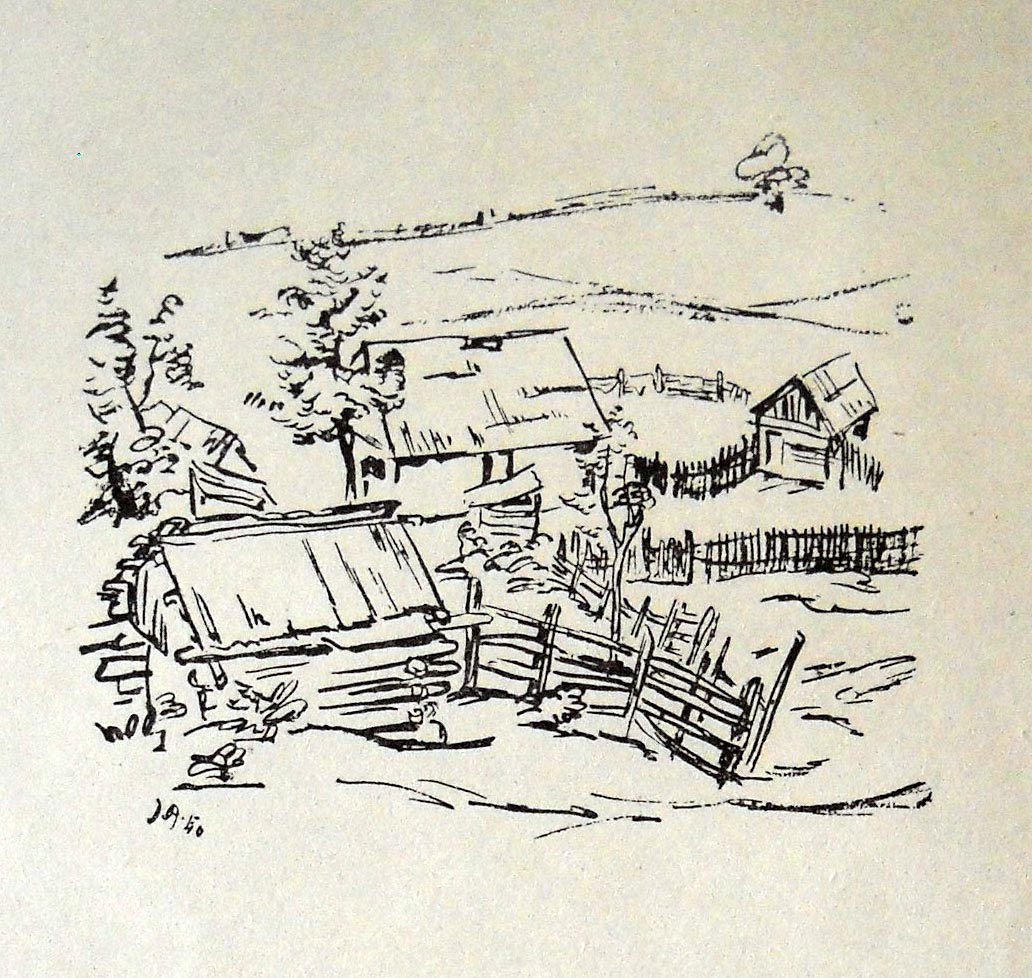

Dvoriste 1940 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Autoportret |

![]()

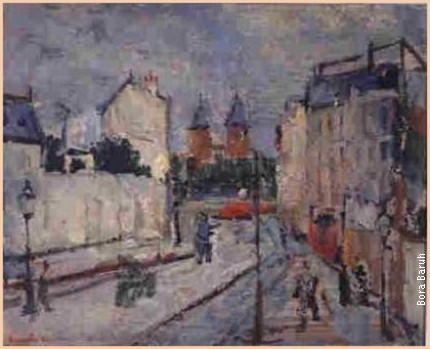

Bora Baruh (Beograd 1911 - Jajinci 1942) <link>

Studirao prava u Beograd, otiso u Pariz na slikarstvo, proteran iz Francuske zbog pomoci Spanskim izbelgicama za vreme gradjanskog rata. Ucestvovao u NOB do 1942 kad je uhvacen i streljan u Jajincima. Slikao mrtve prirode, portrete, motive Beograda i Pariza u poetskom realizmu i impresionizmu.

![]()

By the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, mainly as the result of emancipation and acculturation processes, appeared first Jewish artists in the territories which will eventually become Yugoslavia. They stemmed from the two contrasting worlds. Thus, the Ashkenazic community of Zagreb gave such artists as Artur Oskar Aleksander (1876-1953) and Oskar Herman (1886-1974); while in Sephardic communities of Belgrade and Sarajevo worked Leon Koen (1859-1935 ) and Daniel Kabiljo (1894-1944). After studies at the Art Academies and schools of Vienna, Munich, Paris and London, they returned home to participate in local art movements, devoting some of their work to Jewish subjects. These works, especially in the case of the little-known Sephardic artists, such as Kabiljo, shed light on the traditional world they came from, as well as on their personal search for an identity torn between their own Jewishness, their non-Jewish milieu, and the West, which they had encountered during their studies.

After the foundation of the Yugoslav state in 1918, the Jews, finding themselves united in one geopolitical entity, tried - like their non-Jewish neighbors, the Eastern Orthodox Serbs, Roman Catholic Croats and Muslim Bosniaks - to define themselves as a single community. Between the two World Wars, Jewish artists in Zagreb, Sarajevo and Belgrade, like Ivo Rein (1905-1943), Daniel Ozmo (1912-1942) and Bora Baruh (1911-1942), who had studied in local art centers or in Paris and participated in contemporary European art movements, often expressed in their works their leftist political affiliations, especially with the rise of anti-Semitism and Fascism.

During World War II those and other artists who had been active before the war created a body of art which depicts and interprets their Holocaust experience. There are pictures depicting the life among the imprisoned communists and the life among partisans; drawings and watercolors created in the death camp of Jasenovac, in the pro-Fascist Independent State of Croatia; and the art works showing scenes from the POW camps in Germany and refugee camps in Italy.

Among the artists depicting the life among the imprisoned communists and the life among partisans probably the best one known today, not so much due to his art work but rather due to the important role he played during formation of the new, Tito's Yugoslavia, was Mosha Pijade. Pijade was born in 1890, to a prominent Sephardic family whose ancestor, Uziel Joseph Pijade, a merchant, came in 1830s from Vidin, Bulgaria probably attracted by the Prince Milosh's renewal of Serbia and the freedom of trade, which included the Jews. He settled in Dorcol, the traditional Jewish Sephardic area of the city. Pijade's father, Samuel-Samuilo became famous Belgrade textile merchant, moved to more rich quarters and married Sara, a daughter of the well-to-do Ruso family from Bulgaria. The couple had six children, four sons and two daughters. The boys received high education finishing medical and engineering schools abroad. Most of the family did not survive the Holocaust and perished in the Nazi camps surrounding the city – Topovske Supe, Banjica and Sajmiste, along with other 10 755 Belgrade Jews which was 94% of the city's Jewish community.

It seems that it was David Pijade, the older brother, who was an engineer and bank accountant, but also a poet who encouraged Moshe to pursue the artistic career. Thus, not doing so well academically but talented in arts, Moshe, at the age of 15, enrolled into a local Arts and Crafts School. The following year he already left Belgrade for Munich. In 1907 Pijade started there to study at the Academy of Arts but left after two years and moved to Paris in search of modernism. There he was mainly fascinated by the work of Paul Cezanne and Edouard Manet. Pijade's 1916 "Self-portrait with Japanese Dolls," painted much after this encounter, in Belgrade, still pays a tribute to the great French painter, himself interested in Japanese art, as shown on Manet's "Portrait of Zola", where Japanese prints appear decorating the wall of the writer's study. Pijade's encounter with Paris was short mainly due to a difficult financial situation since his father fell into debt. Upon return to Belgrade in 1910, Moshe started to work as a journalist and continued to paint, living in a rented room on Dorcol, the area where once his grandparents lived. He also at the time worked as a translator, among others translating Baudlaire's poetry.

However, soon the journalism took over along with Mosha's growing identification with Serbian cause during the World War I and sympathies for the leftist political ideas. In 1920, in the newly established kingdom of Yugoslavia, he joined the emerging Communist party which was soon to be outlawed. Within the party, Pijade quickly rose to the leading positions. The publishing of the illegal leftist newspaper which he started, led to his imprisonment in 1925. He was put on trial, sentenced and spent the following fourteen years in prisons. Still, he managed to continue with his revolutionary activity there, since large numbers of the regime opponents were jailed with him. Among others he managed during that time to translate Karl Marx's Capital into Serbian. In prison he also created a number of drawings and few paintings, such as interior of his cell or a self-portrait from the prison, along with portraits of his fellow imprisoned comrades.

Immediately after the beginning of the World War II, which for Yugoslavia started on April 6, 1941 with heavy bombing of Belgrade, Mosha Pijade joined the partisans. Soon, invited by Tito, whom he knew and befriended while in prison, he was invited to join the Supreme Headquarters where he fulfilled different high positions along with preparation of the legal base for the new country and organization of its news agency (Tanjug). Although rarely, he still occasionally created paintings and drawings of landscapes and scenes depicting the life with partisans. After the war Pijade was elected as people's deputy in the National Assembly and represented new socialist Yugoslavia as a member of its parliamentary delegation on number of conferences and meetings in Paris and London.

Due to the fact the he was since 1939 married to a non-Jewish woman and active as a high-ranking Party and State official, Pijade is considered entirely assimilated into his Serbian and Yugoslav surroundings. The possible ties with his brothers and sisters (all of whom were killed by 1942) and other members of the Jewish community during the tragic years of the Holocaust, are still not examined. However, one of the events proudly quoted in the post- WW II Yugoslav- Jewish sources is his participation in the first service held after the liberation in the Ashcenazic synagogue in Belgrade. Since the Sephardic synagogue was destroyed and the Ashcenazic, where they met, used by the Nazis during entire occupation as a brothel, the first gathering of the remnants of the Belgrade Jewish community of which only 1,115 or 6% survived, was especially moving. According to the written memories of one of the participants, Pijade, dressed in the army uniform with medals on his chest was crying. Among his last works is Self-portrait, painted 1955, two years before his death.

Although communist, partisan and national hero as well, Bora-Baruh Baruh is today better known as a Belgrade artist. Born in 1911 to Eliyahu-Ilija and Bulina Baruh, a struggling family of a tailor, he spent his earliest childhood in Dorcol, the Belgrade's Jewish area. At the age of three, at the outbreak of the World War I, the family, by then including two more boys, moved out of Belgrade – the father joined the Serbian army, while the boys and the mother, expecting her first daughter, moved to her hometown Vidin, Bulgaria, to her parents. It was there that the brothers attended Jewish elementary school – the meldar. At the end of the war, finding their house and shop burnt and destroyed, the family, soon numbering six children – three boys and three girls - started its wanderings through Serbia, moving from one provincial town to the other in search of better life. Bora started seriously to sculpt and paint in his high-school years in Niš and organized there a first studio with his school-friends. However, as it often happened in poor Jewish families, the art wasn't considered a serious choice, and Baruh was sent in 1929 to Belgrade to study law, a much more practical and respectful profession. Soon the whole family followed him and they resettled to Belgrade for good.

Although a good law student, Baruh did not abandon his love for art and continued to learn privately from several local artists whose studios were in Dorcol. He opened his own studio in 1933 with the help of the Jewish Community which allowed him to use the premises of the Jewish School in Solunska Street. The same year, 1933 he participated for the first time in the exhibition of the young Belgrade painters shown in the main city's Art Pavilion. The critics wrote about Baruh's art as "recalling impressionism" but were still uncertain about his talents.

Although wishing to spend all his time painting, due to financial difficulties of the family, immediately upon finishing the law school, he started to work for a law firm. He and his brother Isaac supported now the entire family since his father lost his job, apparently because his sons became affiliated with the leftist circles. This seemed to cause friction inside the family and the father left them. In spite of all this Baruh continued to work as an artist as well. The Jewish Community assured him another studio, now in the community's building itself. His main subjects from that period are city landscapes, interiors and still lives. In 1935 Baruh also experimented with the art criticism himself: he wrote about the life and art of Leon Koen , another Sephardic Jewish artist from Belgarde who died that year. Baruh's text, published in the Zagreb Jewish paper Židov, accompanied the commemorative exhibition of Koen's works held in Belgrade. Finally, in the same year Baruh left his hometown for Paris in order to continue his art studies with the stipend of the Belgrade Jewish welfare society Potpora (Support) and a private donor.

However, in Paris, the young painter mainly associated with Serbian artists and shared with some of them studio but only partially enjoyed their bohemian life, working at odd jobs in order to supplement his stipend. Impressed by Pissarro but also Cezanne, Baruh brightened his colors and experimented with form. For a short while he studied as well in the private school of the French artist Amedee Ozenfant, the founder of purism - the extreme form of cubism, bordering with abstraction. In the three years he spent in Paris Baruh participated in a number of group shows and salons, mainly with other Yugoslav painters, sold few works and regularly sent paintings home to be exhibited at the Belagrade exhibitions.

Aside from intense artistic life, while in Paris he became more and more active in the political life of the left. He became the member of the Yugoslav and French communist party and even at some point served as the main contact person for all volunteers coming from Yugoslavia to fight in the Spanish civil war. He provided them with temporary lodgings in Paris, false documents and helped them to reach Spain. These activities finally led towards his expulsion from France, and the fact that he was by then married to a French-Spanish woman Elvira Julie, herself of the leftist orientation, and a father of a baby-boy - did not help.

Upon his return to Belgrade, Baruh was immediately arrested and questioned about his activities within the outlawed Communist Party. However, due to the lack of evidence he was soon released. Still, he remained under constant supervision of the police and had to report to them regularly. This was the beginning of Baruh's double life: on one side it included his illegal work for the Party and on the other the intense artistic activity. Thus, he held his first one-man show in the autumn 1938, where there were exhibited around 40 works. The Jewish paper Židov reported about it with pride. The local critique also accepted the show with lots of praise and Baruh finally entered as a recognized artist the Belgrade artistic scene. Among the exhibited works of special importance was an oil painting "Refuges (sketch for a composition)" of 1938. It was Baruh's vision of the renewed tragedy of the Jewish people inspired by the German capturing of Checoslovakia's Sudettes in 1938, and the growing threat of Nazism. The group of people thrown out of their houses in the middle of nowhere became with this painting for Baruh a threatening vision which re-emerged several times in his following works.

The next, and last, one-man-show Baruh held in 1939, in Zagreb. Although the critique wasn't to sympathetic, he managed to sell so far the largest number of paintings and used part of the money to take his young family, which in the meantime joined him in Belgrade, to the Adriatic coast. The works created there are full of light and joy, expressing rare moments of happiness and relaxation.

The change occurred by the end of the same year, when the police rounded up most of Belgrade communists and as a punishment for a big leftist and anti-Fascist demonstration held in the city, deported them to Bileća prison, an old Austro-Hungarian fortress on the boarder with Montenegro. Among deported were Bora Baruh, his brother Joseph-Joži, Moša Pijade and several other Belgrade Jewish communists. It was there that Baruh decided to start using his art as documentation: to draw and paint in order to depict what he sees, to express the misery and pain. Moša Pijade, portrayed by Bora Baruh while drawing, supported his young friend in this decision.

The Baruh brothers were just released from Bileća in time to arrive home for the beginning of the World War II and the bombing of Belgrade. While running out of the city with his family he was separated from his wife and son and they re-united only a month later. By then Bora became a "Jew" – marked by a yellow band on his sleeve and forced, together with other Belgrade's Jews, to daily clean the ruins left by bombing and pull out the dead. Baruh's pen drawings show the destroyed houses of Belgrade and the cleaning among the ruins. At the same time, in the evenings, he paints portraits of the loved ones and himself, now in dark colors, seemingly having a need to capture them in those tragic moments and give them the eternal life of art. The theme of expelled refuges appeared again in several drawings and oil sketches. Along with this he used the traditional Pietŕ iconography in order to depict the actual scene he saw while running away from the bombed city: the mother mourning above her dead son.

After escaping from a roundup of Jews and warned by a communist friend that Gestapo is looking for him, Bora Baruh was transferred by the Party to the liberated area in the mountains and joined the partisans. There, meeting old artist and communist friends from Belgrade, he initiated organization of an art workshop, whose main aim was to create art works, mainly posters, graphics, slogans, newspaper covers etc. that would serve as propaganda for partisan's and communists' cause.

At the beginning of 1942 the fighting between the partisans and Germans was especially heavy and Bora Baruh's unit was almost destroyed. In order to save those who stayed alive, the commander decided that the fighters should go into hiding among the contact people and wait for further instructions. Bora, believing that for him as a Jew there was a little chance to remain in this rural area illegally, decided, also because he was extremely worried about his family of which he did not know anything, to return alone to Belgrade. The friends tried to convince him not to do that, but he insisted. He was captured on the way by Chetnicks who handed him over to Germans. This was the beginning of a long and painful death path that this Jewish painter had to endure. He was moved from one provincial prison to the other, interrogated and tortured – both as a partisan and as a Jew. These months are relatively well documented thanks to the people who met him in the prisons and later recalled those meetings. Thus, we know that even in such circumstances he managed often with help of others to obtain a pencil and a piece of paper or cardboard and mainly portray the fellow prisoners. Those drawings, 12 of them, were preserved thanks to brave people who smuggled them out or saved them and took them with them when they were let out of the prison. In addition of those portraits he drew again a sketch of the "Refugees" composition. The surviving prisoners recalled that for him creation of art was more then just a skill, it was life itself. In Valjevo prison Baruh was also forced to paint a portrait of a German officer who sat for him as a model. Bora took these sessions especially hard, feeling he is betraying himself.

From the provincial prison he was after several months transferred to the Gestapo prison in Belgrade. Even there he was still drawing. According to the memoirs of the fellow prisoners that survived he used little pieces of paper saved in his pocket and drew his own wooden clogs lacking soles and the prison guards. On July 2, 1942 he was transferred to the concentration camp on Banjica. There he did not draw anything any more. Two days later he was shot in Jajinci.

Baruh's wife and son survived the war as well as one of his sisters. His two brothers died in partisans while all the others were killed in Banjica camp. All the children of Baruh family were after the war declared national heroes and there are streets and schools in Belgrade named after them. Bora Baruh left about 200 paintings and the same number of drawings, however lots of his works found their ways into private collections and it is not yet known where all of them are. Still, a number of them reached the museums or remained with his wife and sister and there were often shown in various Belgrade group shows, while his name entered the history of modern Serbian painting.

The story of Daniel Ozmo takes us to another big and old Sephardic community and illustrates the destiny of many young Jews from Sarajevo caught in the turbulent time of the World War II and the Holocaust. Ozmo was born in 1912 in Olovo, a small Bosnian town, to Lea and Haim. He was one of eight children and the family was very poor. However, soon after Daniel's birth they moved to Sarajevo and he grew up in this city. Ozmo studied at the Art School in Belgrade under Prof. Ljuba Ivanović, then famous graphic artist, but also took classes in sculpting and watercolor. Upon finishing his studies in 1934, he returned to Sarajevo – something most of young Sarajevo intellectuals in schools elsewhere did not do, considering the Bosnian capital too provincial. Ozmo however hoped to be able to financially help his family and started to work in a local high-school as an art teacher. However, in 1937 he was expelled from that post on the pretext that he was a communist and that he with his leftist ideas harms the school youth.

From 1934 until the beginning of the World War II Ozmo participates in the group exhibitions in Sarajevo and in two occasions (1939 and 1940) in Belgrade as well. His first known linocut, the technique with which he created some of his best works, is his 1937 "Self-portrait", extremely expressive and showing influences of Franz Masserel, the Belgian graphic artist whose work Ozmo saw and became interested in while studying in Belgrade. In 1938 he joined the newly founded Sarajevo avant-garde group Collegium artisticum, in which participated mainly young Jewish intellectuals: the musician Oskar Danon, the architect Yechiel Finci and the dance choreographer Ana Rajs. The group published their manifest in October 1939 stating that their main aim is to elevate the culture in their city and to actively participate in raising the consciousness of its people, regardless to their national and religious affiliation. They wrote that they are a group of young artists not interested in their own selfish entertainment, but ready to act and commit itself for the good of the people. To achieve this Collegium artisticum combined the contemporary art with the social aims in the framework of an avant-garde, synthetic theater which was to unify all the forms of art with life. They were aware of and used similar examples developed in Prague (D 38 E.F. theater) and Moscow (Meyerkhold and Tairov) – which is really fascinating, considering the city's provincial character. The group organized theater performances, art exhibitions, concerts with accompanying explanations and lectures in various fields of art. Aside from participating in exhibitions, Ozmo directed also a play by Irwin Shaw, Burry the Dead and delivered a lecture entitled In the Service of the People.

In such spirit of avant-garde art and social awareness Ozmo created in 1939 his album of 20 linocuts entitled "From Bosnian Woods". Taking for his subjects the work of low paid wood-cutters and sawmill workers in the woods surrounding his birth place Olovo, he created a unique series of images combining local, Bosnian atmosphere, German expressionist style and social awareness. The similar style he used in his scenes depicting the night life of Sarajevo coffee-houses simultaneously filled with local charm and Munch-like eeriness.

Among the saved works from that time it is possible to find a few water colors such as one showing the interior of a peasant hut and a drawing showing an old Jewish woman, created in 1939. However, his oil paintings and sculptures were almost entirely lost.

At the beginning of the War in Yugoslavia, in the second part of 1941, Ozmo the member of the Communist Party since 1939, decided to leave Sarajevo for the mountain Romanija in order to join the partisans. However, while leaving the city he was betrayed by his contact person - who turned to be a double agent - and caught by Ustashe who transferred him to the concentration camp Jasenovac.

The camp Jasenovac, was established already in summer 1941, after the foundation of the pro-Fascist Independent State of Croatia. It lied on the river Sava and included five camps, four near the village Jasenovac, and the fifth a bit down the river, near the place Stara Gradiška. Most of the camp was formed on a confiscated estate which included a brick factory, a chains producing factory, sawmill, and an electric plant. Upon opening of the camp the arriving prisoners were sent to work in those factories. The camp in Stara Gradiška was situated in an old fortress, once prison, and there Ustashe opened about fifty artisans' workshops, among which were: ceramic workshop, engraving workshop, sign painting workshop and others. The idea to open such workshops actually came from the Jewish community in Osijek which paid for necessary tools, all in hope to save the imprisoned Jews from the heaviest physical work and certain death. In those craft workshops worked about 500 Jews under somewhat better conditions then they were in Jasenovac itself. According to the memoirs of one of the survivors, in 1942 there were six prisoners in the ceramic workshop among which two painters and a sculptor. One of those painters was Daniel Ozmo.

As Bora Baruh drew in prisons in order to record what he saw and express his feelings, so did Ozmo. About twenty of his drawings were saved and they present today a precious legacy. Among them are several portraits of his friends from ceramic workshop, who drew him also. However, when we observe today his other works, knowing at the same time about the terrible atrocities performed in Jasenovac and cruel killings of Serbs, Jews, Gypsies and all the opponents of the Ustashe regime, Ozmo's drawings and watercolors seem to be calm, even pastoral, observing the scenes from large distance, from above…. Although he believed in the necessity of unification between art and life, as he proclaimed in Collegium Artisticum's manifest, it seems here, where the every-day camp life constantly included torture, suffering and death, he has chosen only art. It probably helped him to maintain sanity and to encourage other prisoners by telling them that the liberation is approaching, that partisan units are coming to free them. He was shot on September 5, 1942 for "spreading the alarming news." Few days before him, his mother, sister and brother were killed. None of Daniel Ozmo's family survived the war.