|

“Giovinezza, Giovinezza,

“Youth, Youth, Verses of the Fascist anthem |

Seven days before Germany and Italy attacked Yugoslavia I left my hometown Zagreb for Split, the main port of former Yugoslavia. I was sixteen years old and hoped to board a ship to escape from imminent war and German occupation. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a single ship in the port, they had all already departed. The war started on April 6, 1941 and after a short-lived defense by the Yugoslav army the country was divided between the Germans and the Italians. Split became the center of the Italian occupation zone. My parents managed to escape Zagreb and joined me there in July. In the fall of 1941 the Italian authorities started deporting to Italy those suspected of collaborating with Tito’s partisans and Jews who escaped from German occupied territories. Thus on November 2, 1941 my parents and I were arrested and put on a ship for internment in Italy. I remember well how my father and I spent that cold night seated on the deck. We talked about what we could expect in the murky future. In the morning we reached Trieste. We got a hearty welcome from the Carabinieri, the Italian military police. They loaded us onto a train. In each compartment there were five male Yugoslav Jews chained together (including my father and me) and three Carabinieri in the remaining seats. When one of us needed to go to the toilet, they liberated him from the chain and accompanied him. This is how my “Italian holiday” started.

We realized that the train was going westward along the Po valley, not as we feared northbound into Germany. We arrived towards the evening in Asti (in Piedmont). The chains were removed and we exited the train. We were escorted by Carabinieri through the streets of the city. Now, we witnessed an unexpected event. As we walked, the people in the streets, mostly women, started yelling at the Carabinieri: “What are you doing to these poor people?” This was the real welcome by the Italian people. It raised our morale.

We spent that night on benches in a public building, it could have been a school. The next day we were separated into smaller groups and sent into different localities. Our group ended up in Castelnuovo Don Bosco, a small town twenty kilometers east of Torino. The Italian authorities treated us as “civilian prisoners of war”. The owner of a local print shop rented a small apartment in his house to my parents. Like everyone else, he and his wife were very nice to us. We lived freely in the town, we were just not supposed to leave it. I used a good deal of my time to study Italian and soon I spoke the language relatively well, so it became easy to communicate with the local people.

Later, my brother Vlado managed to join us after spending some time in internment, near Padova. After seven months in Castelnouvo Don Bosco of a peaceful, but not worry free life, my brother and I, along with several young men, were again taken by the Carabinieri and transported by train to Calabria. I hardly remember any details of this trip. So, taking into account the distance from Trieste into Piedmont and from Piedmont into Calabria I enjoyed the ‘hospitality’ of a free train ride of more than 1000 miles at the expense of the Ferrovie dello Stato, the state railways. As far as our escort is concerned it was at the expense of the Arma dei Carabinieri, the military police.

Our parents remained in Castelnouvo Don Bosco until July 1943 when Mussolini was overthrown and when he later established the Fascist Republic Salό under German control. They had to escape and they crossed the mountains into Switzerland near Lugano.

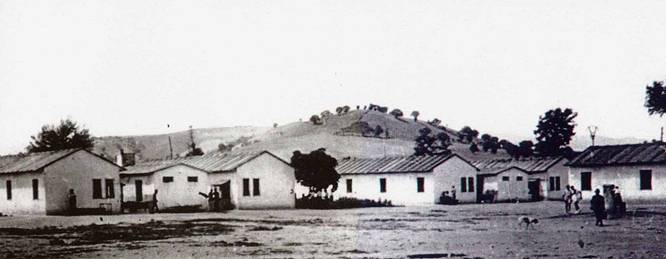

We ended up in the concentration camp Ferramonti di Tarsia, province of Cosenza. After the so called “free internment” in the North, what followed was real imprisonment under truly very tough conditions. It happened to be the largest concentration camp in Italy with a particular history. In the late 30’s a contractor, who had influential Fascist connections in Rome, got a contract to dry up a swamp connected to the river Crati. He never finished the job, but managed to get a contract to build a concentration camp. He converted the barracks he used for the workers and built many additional ones. In total there were some ninety barracks, housing the prisoners, the guards and the administration of the camp. In each barrack there were approximately thirty prisoners. The camp was surrounded by a barbed wire fence. Eighty “black shirts”, Fascist militia, controlled the camp from the inside and a police unit was in charge of the outside of the camp. The rules in Ferramonti were very strict: prisoners could not leave the barracks from 9pm to 7am; they were not allowed to keep their passports, train tickets, stamps, playing cards; they could not have cameras or radios; they were not allowed to have more than 50 liras; books, newspapers, magazines in foreign languages were not allowed without special approval; prisoners were not permitted to correspond and receive packages without administration’s approval, etc. If a prisoner found himself near the offices of the authorities when the flag was being raised or lowered and did not salute in the Fascist way, he would be beaten by the militia. Because of the swamp, the camp was exposed to high humidity, mosquitos and malaria. In the winter the camp was flooded and we walked on small dykes to move from one barrack to another. In the summer it was extremely hot, particularly in the barracks. Ferramonti was known as “Il Campo nella Palude” (the camp in the swamp). It was as well called “Il lager di Mussolini” (larger is the German word for camp). It was obviously a perverse location for a camp.

We got two meals a day. In the morning we received a small piece of bread which did not merit a description and a dark colored drink of an unpleasant taste. For the main meal we were given a watery soup with just a few floating chickpeas, (even now, whenever I see chickpeas I am reminded of Ferramonti). We stayed hungry and when we could we bought some food on the black market which existed in the camp. We spared our energy. We didn’t walk much, and for our limited movements we used wooden clogs.

Regardless of the fact that most of the prisoners were young, the unhealthy conditions and poor food caused health problems. I don’t know how many died, most probably there were more than the 37 Ferramonti graves in Tarsia and Cosenza.

When we arrived in Ferramonti there were over 2000 prisoners. There was quite an international composition of prisoners. About 75 to 80 % were Jews from different countries. The Italian anti-fascists and Jews were in relatively small numbers. More than 100 prisoners came from the Italian occupation zone of Yugoslavia, suspected of collaborating with Tito’s partisans. There was a sizable group of Greek anti-fascists. 70-80 Chinese prisoners, among them were crews from ships in the Mediterranean. Approximately half of them were pro Mao and the other half pro Chan Kai-shek.

When we arrived, my brother, our friend SreŠko and I were sent to a barrack in the northern part of the camp. We each got a sack which we filled with straw to use on our wooden plank beds. This was a rather uncomfortable substitution for a mattress. I vividly remember my first night when I suffered from ferocious bed bugs.

In our barrack we had interesting companions. I will try to introduce those who remained more present in my memory. Regardless of origin we communicated in Italian, which was the lingua franca in Ferramonti. Close to the entrance to the barrack were two strong looking Polish peasants who served in the west oriented army of Polish General Anders. Nearby was Mr. Simic, a middle aged anti-fascist from the northern Croatian Coast. We newcomers were located closer to the other side of the barrack. SreŠko was the closest neighbor on my right side, next to him was Vlado. Further away was Mr. Pekeles, born in Odessa, who spent years in Firenze as an art dealer, - intelligent, full of jokes, always in a good mood. Next to him was Panke, a sad looking, taciturn younger man from Berlin. Across from him was Mr. Schnabel a cobbler from Vienna with his son, both were very quiet. Across from me was Dr. Bronner (I do not remember correctly his last name because he was for us just “il dottore”). He was a very strict orthodox Jew originally from Romania, who had already lived in Italy for a number of years. We heard that he was a pulmonary surgeon who took care of the Royal family in Rome. “Il dottore” took care of me when I got malaria and helped me to get over the disease.

Ferramonti was near one of the two roads which connected Calabria with central Italy. In the spring of 1943, for the first time we witnessed German troops using the road to move south to the tip of Calabria and most probably further to Sicily. On July 9, 1943 the Allied forces invaded Sicily. On the road next to the camp we were able to witness an increased traffic of German military units moving southbound. These were very fearsome moments. However, to my knowledge no German military troops entered the camp.

On July 24, 1943 Mussolini was overthrown, arrested and Marshall Pietro Badoglio formed a new government. In less than a few hours the Fascist militia and the police disappeared from the camp. We were free. Next morning my brother, SreŠko and I left the camp with a sizable group of Yugoslav anti-fascists and started to climb eastbound out of the Crati valley into the foothills of the Silla mountains. For the first time after quite a while, I had shoes on my feet and I remember this as the most painful part of the climb.

After a long day of climbing our group arrived at a village. When trying to speak Italian we realized that our lingua franca did not fully apply in this Albanian village. They spoke ArbŰreshŰ, an ancient Albanian language. The villagers on the Calabrian Silla mountains were the descendants of Albanians who left southern Albania in 1463 ahead of the Turkish invasion.

We bought some straw from the villagers and slept on it on the ground. We ate what we could buy from the village, which was extremely meager. My memory of those days is vague; the only thing I remember clearly was sleeping on the ground and going once to the lower hills to check what was happening on the road, to find out if the Germans left and the Allies arrived.

When the Germans withdrew their forces from Calabria, the first British forces reached the camp in mid-September, 1943. Thereafter, we descended into the camp. The advance of the Allied forces through Italy was quite slow, so we had to wait until the major part of southern Italy was liberated. I had a fever when we returned to the camp. ‘Il Dottore’ diagnosed me with pleurisy (from sleeping on the ground) and took care of me. This kept me in Ferramonti for the next two months.

Finally, I managed to reach Bari where in Tito’s army base I ended my ‘Italian Holiday’.

In retrospect, the assessment of

Ferramonti in history was controversial. In the first years after WWII in the

Italian media and academia emphasis was on the fact that in Ferramonti nobody

was killed and the Jews were not delivered to the Germans. Extremely harsh

conditions in the camp were downplayed. It was obviously an intent to show the

world that the Italian Fascists were not comparable to the German Nazis. With

the passage of time the Italian academic historiography more clearly described

Ferramonti as a case of Fascist crime. So, on the occasion of the fifty year

anniversary of the liberation of the camp, the Foundation for Remembrance of

Ferramonti was established and the surviving barracks were converted into a

small museum.

Twenty five years later there was a series of events which focused on Ferramonti, including academic meetings and symposia, documentary films, etc. In January 2014, in Udine, an academic symposium was organized with the participation of the Foundation of Ferramonti, entitled “The Fascist Concentration Camps”. Discussions brought to light that during WWII more than 100,000 Yugoslav civilians were imprisoned in Fascist concentration camps (including those on the Italian occupied territory in Yugoslavia) and thousands of these individuals died from starvation or disease.

All this happened over seventy years ago. I do not remember many persons and events, many details remain hazy. However, I left Italy with an appreciation for the humane attitude and behavior of the Italian people, with the exception of the Fascists.

Nevertheless, a good part of my youth was anything but “Primavera di Bellezza”.

Concentration camp Ferramonti – Year 1942

Days of remembrance of Ferramonti, 25,26,27, and 28 January 2012

Always remember …… never repeat